TEST SITE FOR ART & HOSPITALITY EXPERIENCES

Journeys, Journals and Hospitality

The Rencontres d’Arles Celebrates its 50th Anniversary

12.08.2019

- #unofficialroutes

- #placeofrefuge

- #unabletotravel

Text by Lotte Laub

The Rencontres de la photographie d'Arles in southern France is celebrating its golden jubilee this summer. Fifty years ago, the photographer Lucien Clergue, the author Michel Tournier and the historian Jean-Maurice Rouquette curated the first edition of the photographic festival, which featured three exhibitions in Arles’s local town hall. Today, it is the biggest and most prestigious photography festival in the world. My Body is a Weapon, On the Edge, Living and Rereading are the four interweaving themes of this year’s event, a showcase of 50 exhibitions.

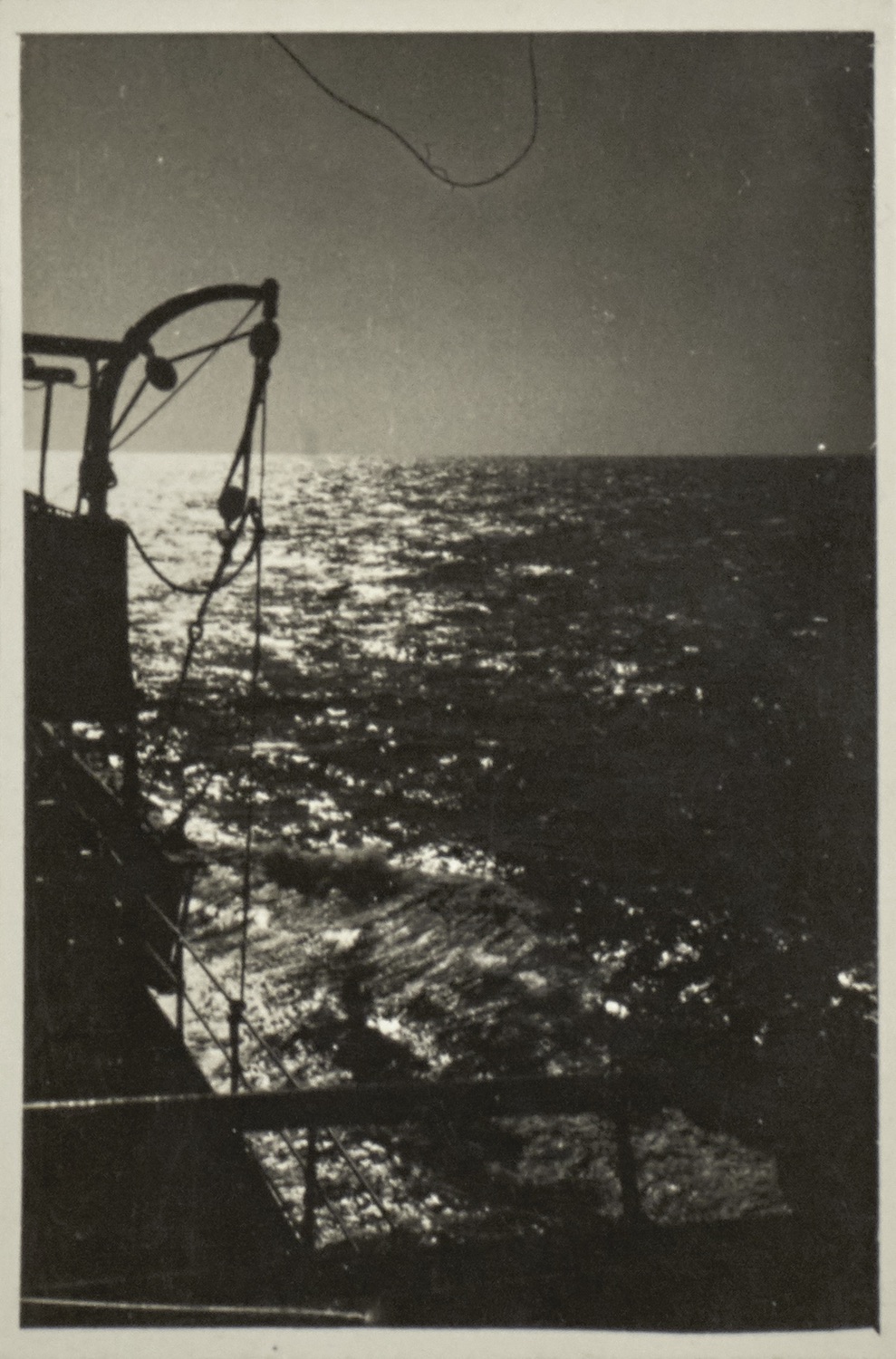

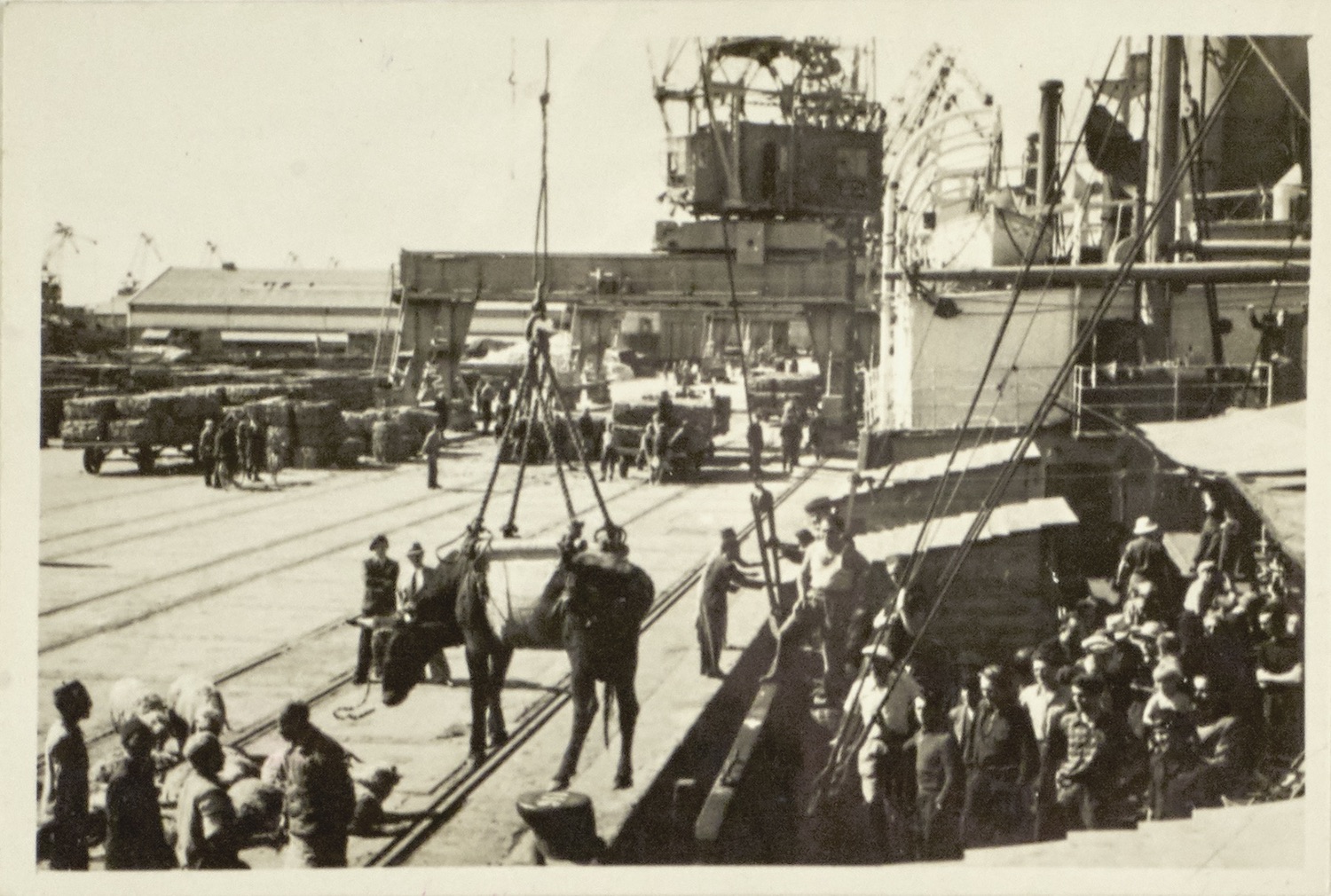

One of the shows in the section On the Edge – A map of horizons and their limits tells the story of an extraordinary journey: Germaine Krull & Jacques Rémy, A Voyage, Marseille-Rio 1941, curated by Olivier Assayas and Adrien Bosc, takes us back to WWII Marseille, then described as ‘the planet without a visa’. In 1940–41, the port city was a crossroads for Europeans in flight, when everyone had only one wish: to get a place on a ship that takes them away from a Europe dominated by the Nazis. Others tried to flee over the Pyrenees to reach the port of Lisbon. Walter Benjamin, who took his own life en route, was one of these. Everyone also had only one fear: to be left behind.

“Leaving France is a titanic task. Usually, when you’ve finally got a visa from an American country and managed to get the exit visa from France [...], you still need the transit visa for Spain and Portugal. When all this is finally done, and it may have taken weeks of effort, the Spanish border may be closed for months, for no reason; and then you notice that the entry visa for America has expired, so you have to start everything all over again.”(1)

These are the words of the German photographer Germaine Krull (1897–1985) who managed to leave Marseille for Martinique on the Capitaine Paul Lemmerle on 24th March 1941. Other well-known passengers on board were André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Victor Serge, Wilfredo Lam, Anna Seghers and Krull’s travelling companion, the young filmmaker and future screenwriter Rémy Assayas, aka Jacques Rémy. They nicknamed the ship the ‘Pôvre Merle’ (‘Poor Lark’), as the captain and crew were die-hard Vichyists and hostile to the passengers from the start. Even though the Antilles route was one of the few routes open, this advantage was reversed on arrival, as at that time the Antilles were administered by Vichy, which meant that, when the ship arrived in Fort-de-France, the passengers were not allowed to go ashore and were instead taken to Pointe-du-Bout and held in a former leper colony.

The show Germaine Krull & Jacques Rémy, A Voyage, Marseille-Rio 1941 documents this journey using previously unpublished photographs by Krull that Rémy’s son and co-curator Olivier Assayas discovered in a drawer at his family’s country home. These pictures are enhanced in the exhibition by original and touching journal entries that reflect the atmosphere at that time.

Back then it was Europeans, Jews, Spanish republicans, stateless persons, surrealist authors and ‘degenerate’ artists who needed to flee Europe. We are familiar with Anna Seghers’s autobiographical novel Transit (1944), which tells of the messy situation for refugees in Marseille and was turned into a film by Christian Petzold in 2018, in doing so changing the setting to Marseille today, an asynchrony that confuses but also imbues past experiences of escape with a moving sense of contemporariness. The exhibition also reminds us that escape and exile is something of a more recent rather than bygone experience, and its location in the famous Cloître Saint Trophime reflects the theme of cloisters as places of refuge and unconditional hospitality.

“Does hospitality consist in interrogating the new arrival? [...] Or else does hospitality begin with the unquestioning welcome?” (2)

According to Derrida, “absolute hospitality requires that I open up my home and that I give [place] not only to the foreigner […] but to the absolute, unknown, anonymous other, […] without asking of them either reciprocity (entering a pact) or even their names.” (3) Thus for Derrida, hospitality has a paradoxical structure. In hospi-talité, both hospes and hostis, guest and enemy, are close together. The question ‘Where do you come from?’ can be an invitation but also an act of control, as in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), in the sense of ‘identify yourself’.

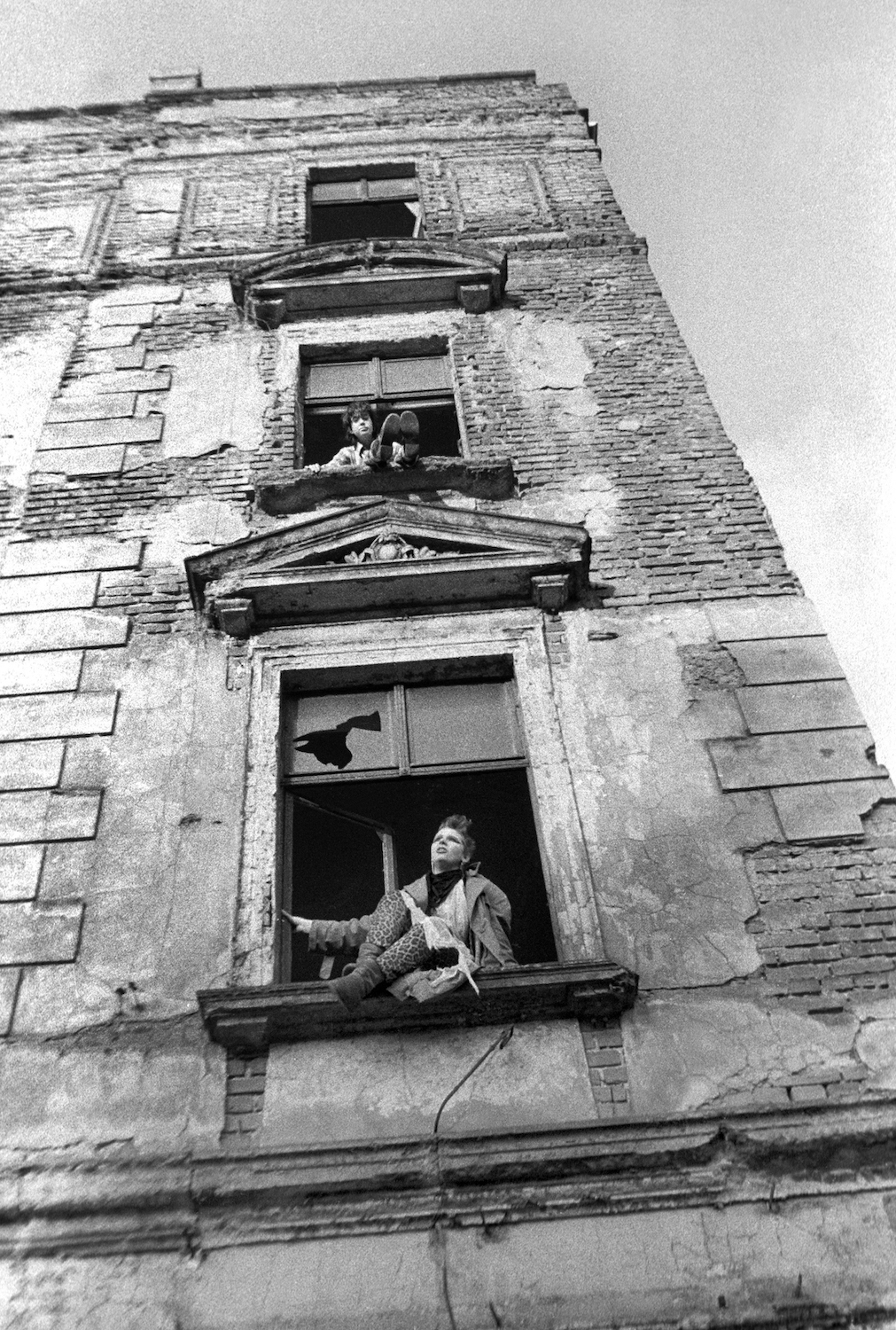

The group exhibition Restless Bodies – East German Photography 1980 – 1989, curated by Sonia Voss, brings together the works of 16 photographers from the final decade of the GDR. In a climate of political stagnation and intellectual powerlessness, artists were spied upon by the Stasi and unable to travel freely. It is therefore surprising that works by Thomas Florschuetz, one of the exhibited photographers, were shown at the Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles in 1987. In an interview, he tells of the unofficial routes that curators from the West took to come to East Berlin, or they were invited by institutions, such as the Centre Culturel Français in East Berlin, whose director Dominique Paillarse was enthusiastic about photography and sent the director of the Rencontres d’Arles, Francois Hébel, to the ateliers of East Berlin artists. However, Florschuetz and other artists were themselves unable to travel to their exhibitions in the West, on the other side of the Berlin Wall, erected in 1961, even though the GDR had in fact signed the Helsinki Agreement in 1975, which among other things stipulated freedom of movement.

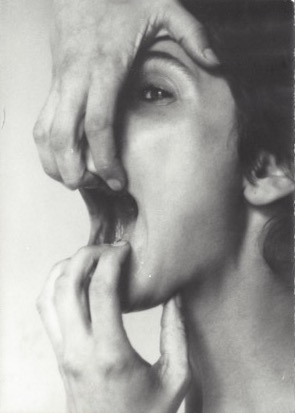

What was in Krull’s exhibition a story of forced travel, escape, exile, and finally liberation from persecution has now become a form of liberation playing out on the inside, in private circles of friends and focused on one’s own physical experience. Dealing with the body, in one way or another, is the thread that runs through this group exhibition, even if the artists themselves have very different backgrounds. They work in the press, teach or live on the very edges of society, for example the artist Gabriele Stötzer. In 1977, after signing a petition against the expatriation of singer and songwriter Wolf Biermann, known for his critical lyrics, Stötzer was sentenced to one year in Hoheneck Women’s Prison – ‘the citadel of murderers’ – for ‘defamation of the state’. It was during her year of political imprisonment among criminals and murderers that she decided to become a writer. According to the curator Sonia Voss: Her “sense of mission was born of her experience in prison.” (4) One day, the Stasi, which had already been spying on Stötzer for many years, even sent a transvestite to incite Stötzer to stage and photograph pornographic scenes, the idea being to use the pictures in criminal proceedings against her.

“In the two days I spent with him, something happened which I was incapable of expressing at the time. I discovered and learned to respect the beauty of a human being with several souls. There was an ease and naturalness with which I was able to photograph this man in all his manliness and able to witness and embrace all of his predilection for the feminine. I was thus able to let go of the belief that I had sole possession of the femininity that I had been trying to claim as my own in all the photographs I had been making. All this created a calm atmosphere of tolerance for the other in and around us, which astonishes me even today. It just happened, without thought and without words – precisely that which art, and nothing else, can do.” (5)

It is ironic that the Stasi sowed the seeds for important shifts in Stötzer’s creative work and her photographs bear witness to her intimate journal, a portrayal of inner self-discovery, in doing so resorting to sensory memories, e.g. of touch, to represent her lived experiences.

Restless Bodies is part of the My Body is a Weapon section, which, according to Rencontres director Sam Stourdzé, focuses on photographers who “shed light on a world in upheaval and at the same time recorded a counter-culture where staging one’s everyday life was an act of resistance against the established order.” Another exhibition in this section is the solo show Evokativ by the newly discovered artist Libuše Jarcovjáková (b. 1952), and which is being curated by Lucie Černá in the Église Saint-Anne. Jarcovjáková has hardly ever been exhibited outside of her home country.

“I was wearing a large Havana straw hat with frayed edges, short trousers and I rode a scooter borrowed from the neighbours. The park was empty but for the school caretaker, who asked me why I wasn’t at school. I told him we were moving to Cuba and that I didn’t have to go to school. Faraway places, trips, adventures... that was what really appealed to me. But the Czechoslovakia of my childhood was a country bordered by barbed wire and you weren’t allowed to travel.” (6)

In what was then Czechoslovakia, it paid to fit in. But behind the closed doors of Prague’s one and only gay club, people could be free. Jarcovjáková visited and photographed the T-Club, which she describes as a kind of family, a place of refuge, almost every night from 1983 to 1985. Taking photographs of her sexual partners and herself naked, masturbating or lying in the bath was risky, so she hid her photographs, her pictorial journal, in a cardboard box behind her wardrobe where they remained until four years ago, when she met Cerná, who lives in Prague. Stourdzé describes Jarcovjáková as the “Nan Goldin of Soviet Prague”. The show leads us into the centre of the church, to a semi-closed off area resembling a place of confession and offering a moving and intimate moment in the exhibition:

“Abortion. I arrived at the hospital in the middle of the night with a high fever. I was bleeding and longed for it all to end. […] I crept silently to the toilet. Jugs full of the urine of pregnant women gleamed on the windowsill. They were wonderful. I took photos of them and did some squats. In the end I miscarried. All that remained were the jugs.”

Similarly to Stötzer, Jarcovjáková moved her choice of motifs to the physical body. Her camera work displays a pictorial density that steers the viewer’s look to the material surface, like a skin that can be touched. The photographs appeal to one’s tactile memory and thereby evoke a feeling of closeness while the overall show offers unshakable evidence of the world immediately around Jarcovjáková and is at the same time a mood piece that is ruthless in its positioning of abandonment and hedonism as an act of resistance.

Les Rencontres d’Arles takes place from 1st July to 22nd September 2019 at various locations in the city.

Header image: Ulrich Wüst, from the Zwischenräume series [In-Between Spaces], Rostock/Berlin, 1985.

- Germaine Krull: “Camps de concentration à la Martinique”, in: Un voyage. Marseille-Rio 1941, ed. by Olivier Assayas and Adrien Bosc, pp. 107–160, pp. 110–111. Author’s translation from the French

- Jacques Derrida: “Foreigner Question: Coming from Abroad / from the Foreigner. Question d’étranger: venue de l’étranger. Fourth seminar (January 10, 1996)”, in: Of Hospitality. Anne Dufourmantelle invites Jacques Derrida to respond, transl. by Rachel Bowlby, ed. by Mieke Bal and Hent de Vries, Stanford University Press: Stanford, 2000, pp. 3–73, pp. 27–29.

- Ibid., p. 25.

- Sonia Voss: “Restless Bodies”, in: The Freedom Within Us. East German Photography. 1980–89, transl. by Darrell Wilkins, ed. by id., Koenig Books: London, 2019, pp. 128–137, p. 7.

- Gabriele Stötzer: “Keeping on Going ‘Til You Come Into Your Own”, in: The Freedom Within Us. East German Photography. 1980–89, transl. by Darrell Wilkins, ed. by Sonia Voss, Koenig Books: London, 2019, pp. 128–137, p. 131.

- Libuše Jarcovjáková, in: Evokativ. Libuše Jarcovjáková, ed. by Lucie Černá, Untitled: Prague, 2019.