TEST SITE FOR ART & HOSPITALITY EXPERIENCES

Leisure Life Bucharest

The artist Sebastian Hosu & the local art scene

17.01.2020

- #bucharestartscene

- #multiplespaces

- #leisurelife

On the occasion of Sebastian Hosu’s solo exhibition Leisure Life at Anca Poterasu gallery in Bucharest, Romania, Cristina Stoenescu and Lotte Laub talk about recent artistic developments and the gallery scene in Bucharest compared to Cluj and Leipzig, about the various challenges galleries currently face, and about the notion of a ‘mobile gallery’.

Lotte Laub Sebastian Hosu studied painting in different places, initially in Cluj-Napoca, then in Turin, Liège and finally in Leipzig, where he lives today. Leipzig with artists like Neo Rauch isn’t the only place that looks back on a painting tradition: Cluj in Transylvania has in recent years produced a generation of painters including Adrian Ghenie, who is also the co-founder of gallery Plan B, or Marius Bercea. Over time, the painting medium had become somewhat overlooked in theoretical discourse, but a desire to deal discursively with this ‘undead’ medium seems to have resurfaced recently. I’m thinking for example about the much-discussed exhibition Now! Young Painting in Germany that is currently taking place at three locations simultaneously and will move to Hamburg next. I’m interested in knowing about Bucharest in this respect. Has it had a tradition of painting? What differences are there between Bucharest and Cluj, in terms of a media focus in art, but also more broadly, for example between the gallery scenes?

Cristina Stoenescu The art scene in Bucharest is configurated in an eclectic manner. There are several clusters of galleries and artist studios: in the North of the city, the Combinatul Fondului Plastic spaces, the University centre exhibition spaces and artistic venues for talks & performances, the old Bucharest neighbourhood around Plantelor street where Anca Poterasu Gallery is also situated. Walking through the city, there are still several important galleries and art spaces that are not associated with any of these clusters, but very much worth visiting.

I focus on the geographical aspect because it does take some exploring throughout the city, in order to get a perspective on the local art scene. The effort is worthwhile since each art space will look and feel very different from any location to the next. Galleries in Bucharest have clear individual characters and a niche they focus on: some on a certain medium, such as painting or photography, others on more emergent or established artists, some prefer to represent Romanian artists only, others focus on a more regional approach.

Art events and exhibitions took place increasingly more frequently during the past ten years, including new artist-run spaces and experimental concepts. Cross-media projects are to be expected in the practice of the art shown by galleries here, involving not only visual artists but also creators from areas of theatre, sound art, architecture, film and literature.

To answer your question more briefly, the Bucharest art scene is much more organically formed in comparison to Cluj’s Paintbrush Factory (which recently closed, just after celebrating its 10th-year anniversary. Centrul de Interese and other spaces throughout the city keep developing, though, it will be worthwhile to see how). Galleries in Bucharest have taken on certain centres and the spaces in-between. The city has an effervescent atmosphere, a place where anything can happen. Art spaces are pushing the envelope on research exhibitions, historical rediscoveries but also on emergent art and experimentation.

In the case of the Cluj school of painting, things are also changing. Younger artists, such as Sebastian Hosu, are creating their own narratives and techniques, sometimes very different from what was being done just ten years ago. I am curious about what you think about "the painting school of Cluj", especially after working with Sebastian? Since the news on Baldessari’s passing, I wanted to ask you how did you see the relationship between photography and painting in Sebastian Hosu’s work? Did it connect in any way to the figurative – abstract theme recurrent in Cluj painting?

LL Baldessari started painting in the 1950s and later resolved to burn all the paintings he had created between 1953 and 1966 in an action entitled Cremation Project, which was recorded on video. He then adopted a cross-medium approach, linking images with language or painting with photography by experimenting with photo emulsion on canvas, in doing so - investigating the boundaries of artistic genres and practising cultural criticism. In that sense, today’s universities seem to be less focused on teaching particular genres or styles and more interested in approaches.

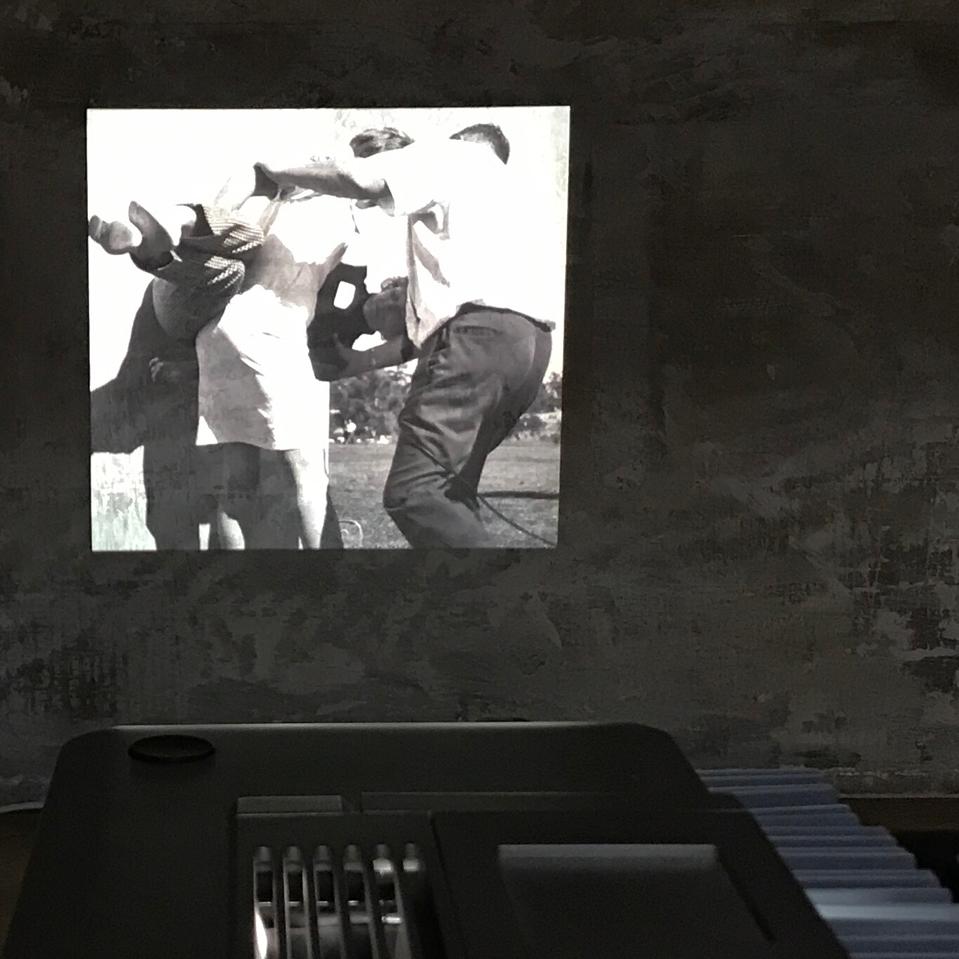

In contrast to Sebastian Hosu, who was born in Satu Mare in 1988, artists such as Adrian Ghenie or Marius Bercea experienced the fall of communism in 1989 and the precarious post-communist era that followed, so in their search for a contemporary expression of imagery in painting, there is maybe a clearer analysis of the ruptures and contradictions of contemporary history. Like Bercea, Sebastian Hosu also deals with the traditional landscape genre, his painting is also invested with a reflexive attitude, but possibly less with the dystopian mood of the kind we’re familiar with from some of the Cluj School works. Sebastian’s works are less about failed utopias, as for him communism was already history and it is archive material from the 1960s and 70s, namely vernacular photography from the GDR, which emerges as a source of inspiration. These family photos offer a view of leisure time in the former East Berlin in the GDR era, between idylls in and proximity to nature on the one hand, but also control on the other, how even one’s leisure life was organised and timetabled by the state. From a contemporary viewpoint, photography being a principally leisure-time activity is already something of a historical phenomenon.

I was particularly interested in Sebastian’s abstraction of the black-and-white photographs into the drawings and paintings, which are at the centre of his artistic practice, namely what is abstracted, his treatment of the black-and-white photographs and his use of colour. On closer look, it becomes clear how moods change with his choice of colour, how stillness becomes a movement and vice versa, and how the exertion of force is expressed by emphasising verticals, horizontals or diagonals, or by changing the distribution of weight – a free-hanging leg here, a leg in support mode there. Sebastian isolates details, enlarges them and paints over them. In his paintings, he avoids narration and illustration and seems more interested in motifs and scenes.

Up to last summer, Anca Poterasu gallery had a temporary space for a year at the Spinnerei gallery in Leipzig. How did this come about? Did you often travel back and forth between Leipzig and Bucharest? How did you experience Leipzig and the art and gallery scene there?

CS It was very exciting to be doing the mobile/satellite gallery space in Leipzig. In 2016 we were invited to exhibit at the Werkschau – Halle 12 for the Gallery Weekend and began discussing then the possibility of more shows in the Spinnerei. We knew that the Spinnerei invites certain galleries to take over a project space for one year and Anca Poterasu had had the idea of a mobile gallery for some years. We were very happy to be one of the guest galleries for 2018-2019, showing seven projects during the span of a year. We had this small yet visible project space, with large windows one could see from entering the compound. The visitors really appreciated showing something different than large-scale installations or just a collection of group shows. The artists travelled with us for the opening on most occasions, so it was great to see how their experience of the Spinnerei fed into other projects that followed.

There was a strong curiosity amongst the local visitors to see either the Same Histories installation of photography and enlarged clothes of Matei Bejenaru or the complex cross-media project of Larisa Crunțeanu, Keep Forgetting to Forget Me. With the support of the Romanian Cultural Institute and funding from the National Administrative Cultural Fund, we gave free-hand to the artists who enjoyed working and experimenting with space.

We are happy to have also worked together with curators such as Mateo Chacon-Pino, Lavinia Freitas and Anja Lückenkemper for some of the shows. It really boosted the ideas between ourselves, the artists and the audiences there. The year full of shows in Leipzig brought, of course, good visibility, which was one of the main objectives of the Stoyan Dechev’s sculptural project Event Horizon that was shown in Plovdiv at a large exhibition part of the European Capital of Culture programmed in 2019 as a direct consequence of his participation in our guest gallery space in Leipzig.

Anca and I travelled back and forth Leipzig-Bucharest in turns, to be able to also prepare for the launch of our new gallery space in Bucharest in June 2019. None of it would have been possible without the constant dialogue with the Spinnerei galleries which made us feel welcome there. We worked with Daria Frei, an up-and-coming curator who was our custodian in Leipzig so we felt that all the pieces were there – working with young and also experienced curators, discovering new partners in the art spaces in Germany, creating new opportunities for our artists. The project ended in August 2019 but continued with collaborations such as the Leipzig Week in Bucharest, where we worked together with Eigen+Art for a group show in Bucharest.

LL Could you say more about the Leipzig Week in Bucharest?

CS There is a strong cultural connection between Leipzig and Bucharest that has been built over centuries, especially in trade (leading to one of the most well-known street names in Bucharest, Lipscani). In 2019, the German Embassy in Romania organized the Leipzig week in Bucharest, full of events and conferences on the historical link between the two cities. In 2019 we most importantly celebrated 30 years since the fall of the communist regime in Romania and the events paid tribute to the important role of the Leipzig Monday demonstrations in the reunification of Germany. Within the framework of the event, Anca Poterasu Gallery and Eigen+Art Leipzig collaborated for a group show featuring artists from both galleries. Anca and I worked together with Elke Hannemann and Franziska Jaster in reinterpreting a show that they first set up in Leipzig, titled not everything means something, honey. The somewhat off-putting title is on a closer read an invitation to disregard known structures in order to be able to free our perspectives on shifting realities. We had a lot of fun showing not everything means something, honey (vol.2) during October 2019, with works from artists Anna Baranowski, Birgit Brenner, Larisa Crunțeanu, Laurette Le Gall, Stef Heidhues, Sonja Hornung, Adelina Ivan, Aurora Király, Kristina Schuldt, Jana Schulz, Hanna Stiegeler and Ulrike Theusner. It was unprecedented for me to be working on an existing curatorial proposal, a dialogue that took place at a curatorial and gallery level, as well.

LL In Leipzig, galleries such as Eigen + Art moved into the Spinnerei – the former cotton-spinning mill, now home to galleries and studios – in 2005, 16 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Cluj has been home to the Fabrica de Pensule or Paintbrush Factory, which is maybe comparable to the Spinnerei, since 2009, so a lot of new developments have taken place in recent years. What is Bucharest like in this respect? Is there also a certain site or area where galleries are located? Has there been continuity, or rather breaks and changes, in recent years?

CS The first private galleries in Bucharest opened during the 1990s, but it’s in the mid-2000s that more and more galleries started functioning with a continuous programme. The Contemporary Art Museum was founded in 2001 (and was officially inaugurated in its current location in 2004). Important exhibitions venues such as Galeria Nouă, Kalinderu Medialab, Galeria Etaj ¾ have come and gone, but still are consequential to the artists and curators working nowadays.

It is important to mention that in 1995 the first department in photography opened at the Arts University in Bucharest at the initiative of Iosif Kiraly, Radu Igazsag, Călin Dan and Roxana Trestioreanu, marking an important step in artistic photography and its recognition as an art form in Romania. There might not be a specific art form prevalent in the exhibitions in Bucharest, but photography occupies an important place.

The contemporary art scene in Romania, seen through the lens of Western definitions is still quite young. It is an exciting time to be exploring it. On one hand, there is a lot of experimental, emergent art with artists travelling and linking with art professionals across the world; on the other hand, there has never been so much interest in re-discussing the past decades in our history by art sociologists and art historians as it has been since the 2010s. While all these changes of perspective take place there are a lot of opportunities for more shifts and even breaks to be happening. The only difference now is that we had had some time to build established venues, awareness and visibility towards audiences from Romania and abroad enough so as the changes do not remain isolated, but would ideally propagate further, creating new models and relations not only towards the West but also relative to our own history and region.

LL It is interesting to note that Bucharest’s contemporary art museum MNAC is located in the Casa Poporului, which is said to be the world’s second-largest government building after the Pentagon. It was built by the Romanian dictator Ceaușescu in the 1980s but the Iron Curtain fell before he could move into it. Whole districts were demolished to make way for his new construction, which is ironically called the House of the People. There were plenty of discussions and rumours about the building’s post-communist fate, but little took place. Today it is home to the Romanian parliament and, at the back, the MNAC. It’s difficult to reach the museum without a car since the building takes up such a large surface area. At the same time, it’s located at a neuralgic point for the city and as such is an intriguing location for a museum. How do you perceive the museum’s location, or how is it perceived generally? By way of contrast, there are also contemporary art galleries such as Anca Poterasu gallery or Suprainfinit in very old districts of the city.

CS The location of the National Contemporary Art Museum (MNAC) has been controversial from the start and there are artists refusing to this day to exhibit their works there. The institution is not a stranger from wide-spread criticism, especially considering the absence of an acquisition programme and its problematic location. However, I find it interesting that even though it is indeed difficult to get to, the Parliament House itself is one of the most visited touristic attractions in Bucharest – a monstrous building attracting many eyes. Another large project, the Orthodox Cathedral that is being built nearby will position the museum in the middle of mass-cultural pilgrimages. I always thought that such an institution can, have the best vantage point to challenge the power relations around it if it chooses to. I personally enjoyed some of its more daring shows at the 4th Floor, where young curators and emerging artists have had some very good projects alongside the permanent collection exhibition launched in 2018, attempting an acknowledged imperfect, but a necessary view of contemporary art in Romania since 1947 to 2007.

LL Anca Poterasu gallery moved to a new location this summer. The gallery is also planning or already running a residency programme at its former location nearby. This is a broad spectrum for a gallery if you also take into account the temporary space in Leipzig and your presence at international art fairs. You also work with other art spaces, including institutions like the Goethe-Institut. How do you approach all these tasks and roles? And how do you see a gallery’s role today, both in Bucharest but also generally? Maybe somewhere between a quasi institution but at the same time operating within the (international) art market?

CS Starting the gallery in 2011, Anca Poterasu has always been aware that the art-scene in Bucharest is still in development, with all the pros and cons of this observation. To have an emerging art space in an emerging contemporary art-scene is difficult, but also immensely rewarding especially since there are no set parameters to what one is building.

The gallery started its own residency programme in 2015, among the first such projects in Bucharest at the time. The residency programme Plantelor 58 is complementary to our goal of representing Romanian artists, is creating opportunities for international exchanges for both artists and curators. Another programme adjacent to the gallery is publishing books for our roster of artists – we are currently preparing for the launch of a painting catalogue of Iulian Bisericaru. The mobile gallery/project space is something that we want to continue after our Spinnerei Leipzig experience. Both Anca and I are very aware of supporting the local art scene as much as we can, to contribute in a way that institutions might have if they were more numerous or more present.

The different roles we are taking on bringing added value to the shows we are doing, to the curatorial programme we are building together with our artists and guest curators. There is a symbiotic relationship between the commercial aspect of the gallery and its non-profit projects, since creating more connections contentwise feeds into better shows, more appealing projects.

To focus on the general context more, the international art market is driving for a specific type of gallery, especially when we think about the curatorial demands of art fairs that only accept a gallery’s participation according to its curatorial programming and history of exhibitions. It is a subtle but efficient way to influence how a gallery chooses to function and apply its resources. There are complex power relations being built and many times we have to stop and question our choices, to continue to do the best of our work and also succeed in supporting our artists and promoting them in high profile events.

I am very interested in how you see this dynamic. Zilberman Gallery exists in two very different contexts – Turkey and Berlin, dealing with many interesting commonalities and cultural differences between the two countries. How have the round tables, publication launches and artist talks supported the activity of the gallery?

LL I’m very familiar with the topics you address. In Istanbul, there are similar tasks that we as a gallery take up as well as diverse roles and also a social responsibility that we assume. For example, once a year we provide young artists with a platform to exhibit their works after being selected by a jury following an open call. There’s also a project space as well as the artist residency programme in Berlin. We produce catalogues for every exhibition and organise talks and other discursive formats with the artists. Around one-half of our artists come from Turkey, the other half from other countries. Both locations are important for the gallery to establish the artists on a cross-border level, especially at a time when galleries are confronted with different challenges and expectations. In this sense, we are also interested in exploring critical artistic research and alternative canon making processes. Mediation between diverse historical, cultural and social traditions plays an important role for us, which we try to facilitate through discussions or the catalogues.

I also find it interesting to discover the new paths that collaborations between artists and galleries can take. The advantage of a gallery is maybe that new ideas can be implemented quickly. The mobility offered by having two locations is also a plus. Could you elaborate a bit more on the notion or concept of a ‘mobile gallery’?

CS The advantage of two locations is indeed the flexibility of options and diversity, it is enthralling to work with artists experimenting with new contexts and artistic languages. The mobile gallery is a concept that Anca Poterasu has been thinking about for some years, trying to find new ways on how to present the artworks of our artists to an international audience.

The main idea is to find a space in a city, such as Leipzig, but also perhaps Brussels, Paris or any other cities in the world and to run a year-long project space. The mobile gallery, the project space would then be focused on creating long-lasting connections with the art scenes there, be part of it for a season of exhibitions and organically interact with visitors, local art professionals, artists and institutions. So far, the guest gallery space in Leipzig has provided numerous opportunities for our artists, working projects with curators and continuations in Bucharest, as well. Rather than being completely dependent upon a few days of an art fair, this experiment allows us to build a constant presence there, where international institutions and collectors have an appetite for discovering something new. A mobile gallery is seen as a torch that passes on from location to location, referencing our permanent space in Bucharest, a way of showing concepts and artistic projects that do not rely on the competition with other spaces, but rather collaboration and openness.

The solo exhibition Leisure Life by Sebastian Hosu is curated by Lotte Laub. It takes place from 15th December 2019 until 31st January 2020 at Anca Poterasu gallery in Bucharest. With the kind support of the Goethe-Institut Bukarest.

Lotte Laub is a Berlin-based curator and arts writer. Since 2016, she has been a Program Manager at Zilberman Gallery, Berlin. She obtained her PhD at the Friedrich Schlegel Graduate School of Literary Studies at the Freie Universität, Berlin. In 2010, she received a research fellowship from the Orient-Institut Beirut and an Honours Postdoc Fellowship from the Dahlem Research School at the FU Berlin. She worked previously at the Gropius Bau in Berlin.

Cristina Stoenescu is a resident curator at Anca Poterasu Gallery in Bucharest. She has graduated from the master programme of the Centre for Excellency in Image Studies in Bucharest and the Arts & Heritage Studies M.A. at the University of Maastricht with a specialization in the history of contemporary art with a focus on curatorship.