TEST SITE FOR ART & HOSPITALITY EXPERIENCES

Leisure Spaces

An interview with Triin Ojari and Epp Lankots on Soviet-era Estonian holiday architecure

22.10.2020

- #holidayarchitecture

- #sovietleisure

- #modernistholidays

Largely unknown to those outside Estonia, the unique holiday architectural heritage leftover from the Soviet period is still in use today. To find out more about the strictly modernist constructions and the political conditions which gave birth to them, we spoke to Epp Lankots and Triin Ojari, co-curators of the exhibition Leisure Spaces, on view now at the Estonian Museum of Architecture.

Where About Now: Where are you right now?

Triin Ojari: At home.

Epp Lankots: I’m at home in central Tallinn and Triin is in the other part of central Tallinn, so there are a few kilometers between us.

WAN: Is there a place you’d rather be?

EL: No, well, perhaps in my country house. Actually, I’m quite happy with this break in travelling that the Covid situation brought along, it’s very nice to be in my home country for a while.

TO: I’m very happy to be where I am, too, sometimes it’s more peaceful to do work from home than in the office where you can be disturbed.

WAN: Can you tell us a bit about your backgrounds and your relationships to the Estonian Museum of Architecture?

TO: I’m an art historian, I studied Art History at the Estonian Academy of Arts and more specifically, I’m an architecture historian. I’ve been working at the Estonian Museum of Architecture for 6 years now and I’m the director of the museum.

EL: The first part of my story is similar to Triin because we are graduates of the same Art Academy. I graduated a few years after and I’m also an art and architecture historian. We work together because our area of specialization is 20th century architecture, especially the Soviet period. I work as a Senior Researcher at the Estonian Art Academy and I’m a guest curator at the Estonian Museum of Architecture.

WAN: The exhibition Leisure Spaces - which is currently on view at the Estonian Museum of Architecture - deals with holiday architecture in 20th-century Estonia. Can you tell us a bit about how you conceived the exhibition?

TO: I think the idea came about 2 years ago and the most intensive working period was last year in the summer when we travelled around Estonia, took photos and gathered information from different places and sites. It’s a subject that is surprisingly not really studied yet in Estonian architectural history; it’s not untouched territory but it was interesting for us to open up new terrain in a way.

EL: Well, I think our interest goes back a few more years. I was already interested maybe 8 years ago about the specific types of holiday buildings in Estonia called company holiday homes which were owned by Estonian companies, factories and institutions. But then we have this really large heritage of the summer cottage architecture. And why choose this subject is well, if you talk about the Soviet period in Estonian architecture or in the socialist world at that time, a lot of research has been done about mass housing estates, standardized housing flats, and how the state controlled the domestic environment. But we could say that the leisure spaces, or leisure itself, was equally as controlled. It’s a vast subject area which received a lot of attention from the 60s onward when they started to develop these areas. It’s a kind of mass phenomenon in itself which is not industrially produced. Like Triin said, it’s not been studied. When you look at Estonia and at the whole Soviet Union, all the former Eastern Bloc countries, leisure architecture has received a small amount of attention.

WAN: It is indeed a very fascinating subject which is not known here further west. What can visitors to the exhibition expect and how can we experience it virtually?

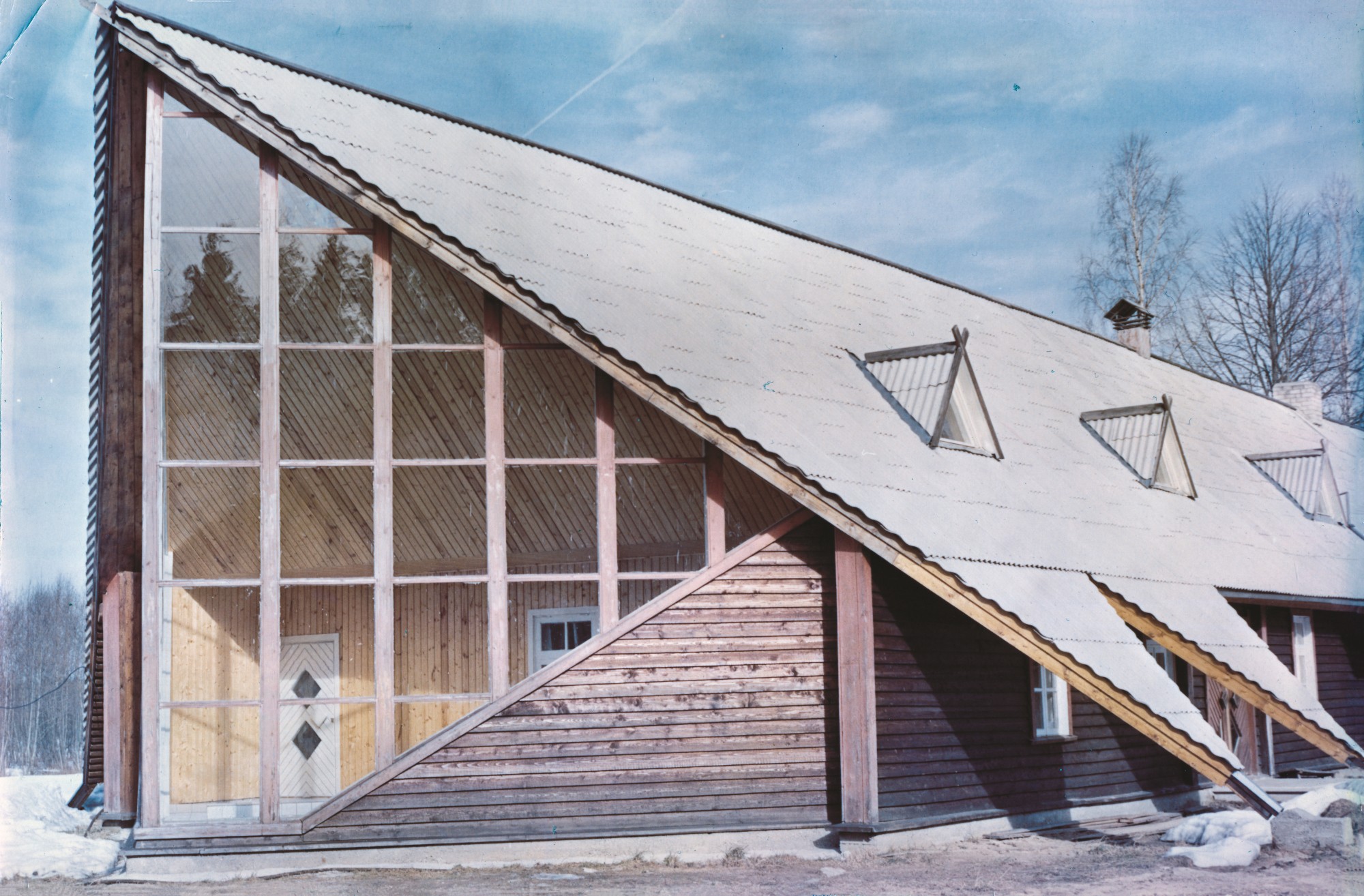

TO: The idea of the exhibition is to put together the two parts of leisure or holiday and how you spend it: is it individual or collective? The exhibition is divided into key words like Summer Cottage Architecture, Garden Cooperatives, A-Frames, Company Holiday Homes, Children Camps and Hunting Lodges, so we could spread out the topic into categories and make it easier to get an overview. We also have videos like a TV show from the mid-80s called Gardener's Summer and some documentaries describing how people had nice times in these holiday homes. Of course, the catalogue and the exhibition complement each other in a way, so there is much more explanation and background given in the catalogue.

EP: Regarding the setup of the exhibition space, it’s something that we cannot mediate to the visitor who is not able to come here. It’s a rather minimalist space with tables which look kind of like buildings; I wouldn’t say they are models of summer homes but maybe refer to that. We also have a meditating area with a 12-minute video on loop. Normally people think it’s a photograph but suddenly a bird flies through and you realize it’s moving.

WAN: So in a way, a visit to the exhibition space is a sort of leisure moment in itself?

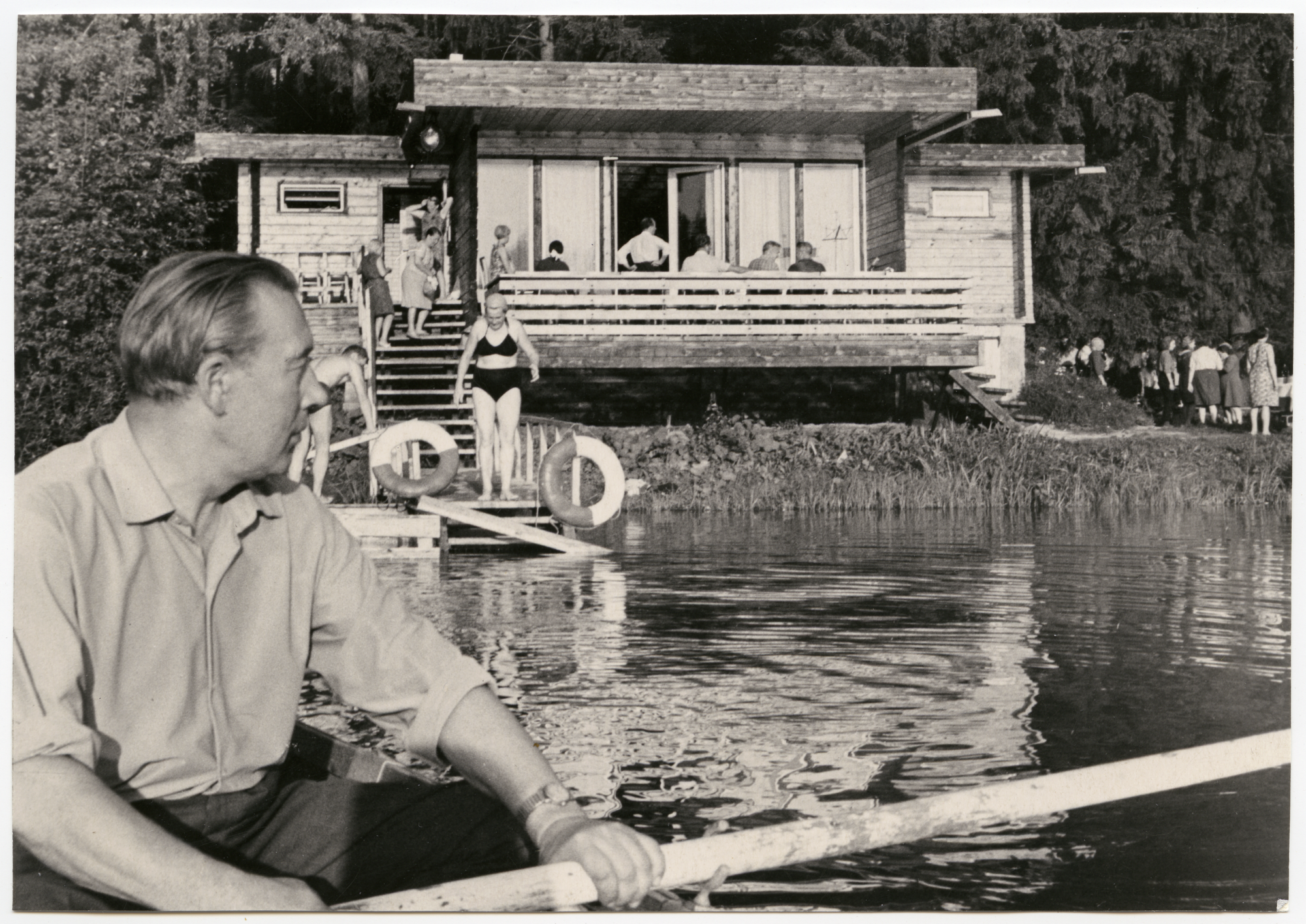

TO: Yeah, we also have the waterfront setup because water or the sea or a lake or a river has always been very important in the mind of Estonians that you have to spend your holidays near water.

EL: There was also a strange twist in the Soviet period because as Estonia was the most western part of the Soviet Union, the northern coastline was the border to Finland. It was heavily guarded so even if you had a summer cottage or holiday by the sea you couldn’t swim just anywhere as there were border patrols. They even had a raked area on the border to the sea so that if anyone tried to escape via boat to Finland, you could see footprints in the sand. So you had this strange mix of seaside holidays with armed guards.

WAN: So, how did the political structures of the time influence the experience of individual workers on holiday in Soviet Estonia?

EL: When you talk about Soviet leisure and Soviet holidays then it all comes down to the worker, to put it rather simply. It’s the worker that counts for the society and it’s very clear in the early Soviet rhetoric. The importance of the worker was very much part of this so holiday institutions were built for workers to improve their productivity and health - it was the worker that was important for the society. First, there were sanatoriums which were just for individual workers but then began the construction of company holiday homes and summer cottage cooperatives. So there was the individual holiday in the summer cottage which was built in a cooperative system, whose members were working together in the same institution, or the company built a separate bigger holiday home for the workers, in which case you could bring your family along, which was not the case in the state sanatorium for instance.

TO: One has to admit also that it was quite affordable compared to nowadays. A holiday in the sanatorium or in the company holiday home was through the unions and workers got a voucher to receive a holiday in the special complex. Regarding the summer cottage cooperatives - by the end of the Soviet period in 1990, Estonia had 54,000 cottages, so there were more than 200,000 people involved in the gardening in summer cottages.

EL: That’s about 13% of the whole population.

TO: The land of the cooperatives were given for free by the state but each plot owner had to build the house on their own. So it took years and years with a lot of effort but it was affordable. Many cooperatives were for the nomenklatura so the higher position officials, but most of them were quite egalitarian so there were directors and simple workers and bookkeepers all in the same cooperative.

EL: In the exhibition we don’t talk about the personal and collective separately; they are very much intertwined.

WAN: It’s interesting this interplay between the individual and the collective. At first, workers took their holidays individually through their employers and the children even had their own summer camps. But then individual families began constructing their own summer cottages in these collectives?

TO: Well, the cooperative was a part of the collective system. Cooperatives were founded by the employees of one company, so all the members knew each other. The board of the cooperative commissioned the planning of the area as well as chose the suitable standard designs for the houses or selected an architect to do the individual designs. The whole process, until the house was finished and received the acceptance from a special committee, was very much controlled. There was also a difference between the summer houses and the garden houses. The garden houses were smaller in size (25 sqm allowed only!) and they had gardens where one had to grow vegetables and fruits. Also, a greenhouse was very common. In the early 1980s the Soviet Union launched the Food Program to feed the population which resulted even more massive garden cooperative movement. Instead of cultivating ornamental gardens, the emphasis shifted to allotments as a productive unit. Cooperatives were the motors behind the whole summer cottage building system ensuring very consistent looking summer house landscape in Estonia.

in Rannamõisa, demolished. Architects Ülo Stöör, Arpad Andreller, 1965–1966. Photo: Viktor Salmre, Estonian National Museum.

WAN: Does this history affect how Estonians take their holidays today?

EL: Well, the summer cottage culture has been preserved in many places. And nowadays it’s other groups that you have holidays with together, like your friends. Back then, it was centered around your workplace and those informal ties were not visible. There has been research around these summer cottages as places where dissidents would gather, also artists and there were big parties. So there were informal networks but the official one was centered around the workplace, and that has changed nowadays.

WAN: What about the cottages and the larger complexes, how are they being used today?

TO: Luckily, many of the architecturally interesting cottages are still owned by the original families or their children who really value the things their parents built. Most of them are not made very durably but they are maintained well and are still used as summer cottages.

and the house with a playful roof was built in 1963. Typically for a summer house, there is a sleeping loft upstairs. Photographs from 2019 by Tõnu Tunnel, Estonian Museum of Architecture.

EL: The average company holiday home was made for 25 people, and they are located in nice natural spots, quite isolated and further away from bigger cities like Tallinn and Tartu. Because there were so many of them, there are many which have been abandoned but some are still used as cheaper holiday destinations for families.

TO: Compared to the rest of the Soviet Union, the Estonian holiday architecture is very unique, even compared to other Baltic countries. They were very strictly modernist. The people really admired and accepted modernist architecture in the woods, so out in the thick woods you have these very simple boxes.

WAN: So, in comparison with the rest of the Soviet bloc, the Estonian architecture was much more modernist?

TO: Yes, more homogenous in that sense because they were mostly standardized and designed by one or two architects so they have a similar look.

EL: If you look at the Russian dachas, they have more of a pastoral longing and this old village architecture with wooden decorations. And Estonians, we’re different. You had to build your cottage on your own, but we really followed this design and built it in all the details. In Russia or Lithuania, the do-it-yourself culture is expressed in really different ways. So the Estonian areas look very integral and neat in comparison to the Russian areas.

WAN: So, what projects are you working on next?

TO: In the museum we will celebrate our 30th anniversary, so our next exhibition is about fantasy architecture, or architecture which can save the world. It’s called The House We Need.

EL: I’m working as a researcher so I plan to write more on leisure. This exhibition and the book is kind of the beginning for me and I want to go deeper into some aspects. Triin and I are also planning on editing a history of Estonian urban planning.

The exhibition catalogue is available here.

Header image: A-frame with the thatched roof in Vääna-Jõesuu. Architect Vadim Chentropov, 1969. Photo Tõnu Tunnel, Estonian Museum of Architecture.