TEST SITE FOR ART & HOSPITALITY EXPERIENCES

In the Exodus

Iranian artist Hoda Afshar uses photography to address issues

04.10.2017

- #intheexodusiloveyoumore

- #migration

- #identity

Born in Tehran and based in Melbourne, Iranian artist Hoda Afshar uses photography as a means to address issues of power relations, representation and identity. We had the pleasure of talking to Hoda about migration, her influences and her artistic process.

Tell us a bit about yourself – where you’re from, your trajectory and your development as an artist.

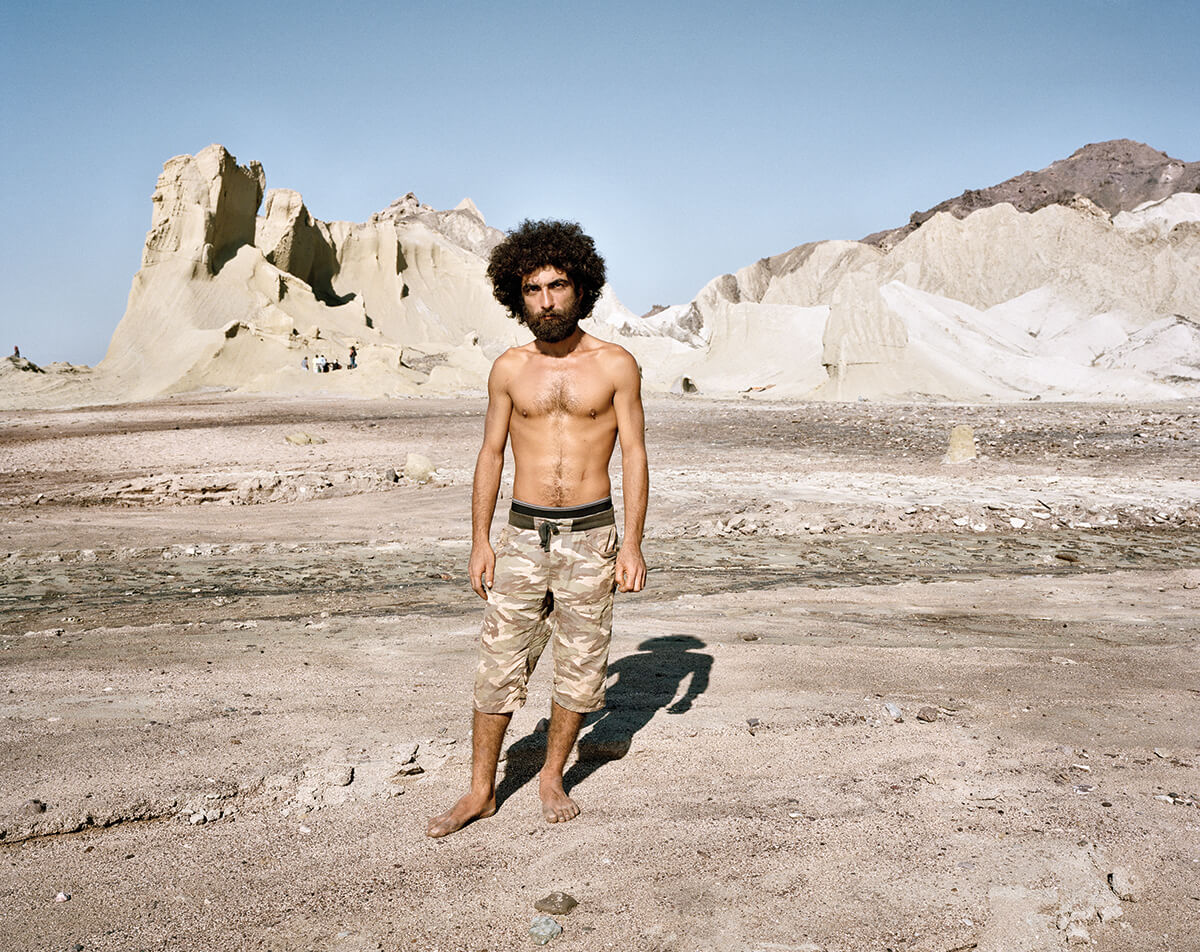

I was born and raised in Tehran, Iran, and after finishing my bachelor degree in photography I moved to Australia to experience life in a different part of the world. In Iran I started my practice as a documentary photographer and also as a photojournalist, photographing different aspects of life in Iran and exploring the issues affecting different social groups, especially minority com- munities. After migrating to Australia the focus of my practice shifted some- what: I began making more staged work in which I explored similar issues, but from a more conceptual perspective, and especially in relation to the lives of non-Western subjects living in the West. So in this sense, I became the subject of my own work – I began reflecting on my own experiences and encounters as a way of approaching larger questions to do with identity and representation. This fed into my PhD research-based practice in creative arts, which I started in 2011. About three or four years ago I also began a new series about contem- porary Iran in which I explore my changing vision of and relationship to my homeland. Throughout this period I have exhibited my images throughout Australia and internationally. The first major exhibition of my Iran series will take place in mid-November in Melbourne.

Are there any particular artists who have influenced your way of approaching photography?

My greatest influences tend to be outside of the photography world. I always find inspiration in literature, theory, other visual art mediums and movies. The artist who has probably influenced my documentary practice the most is the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami. I am also very much inspired by the romanticism and poetry of the work of the video artist Bill Viola. I have also been deeply influenced by the work of the exiled visual-artist Mona Hatoum––in particular, her beautifully distilled way of communicating ideas related to power-relations and the condition of global exile. I love the writings of Edward Said for a similar reason.

Tell us about your process. When framing, setting up a scene, or finding the per- spective that you want to document and represent – how do you translate that through the camera and into the photo?

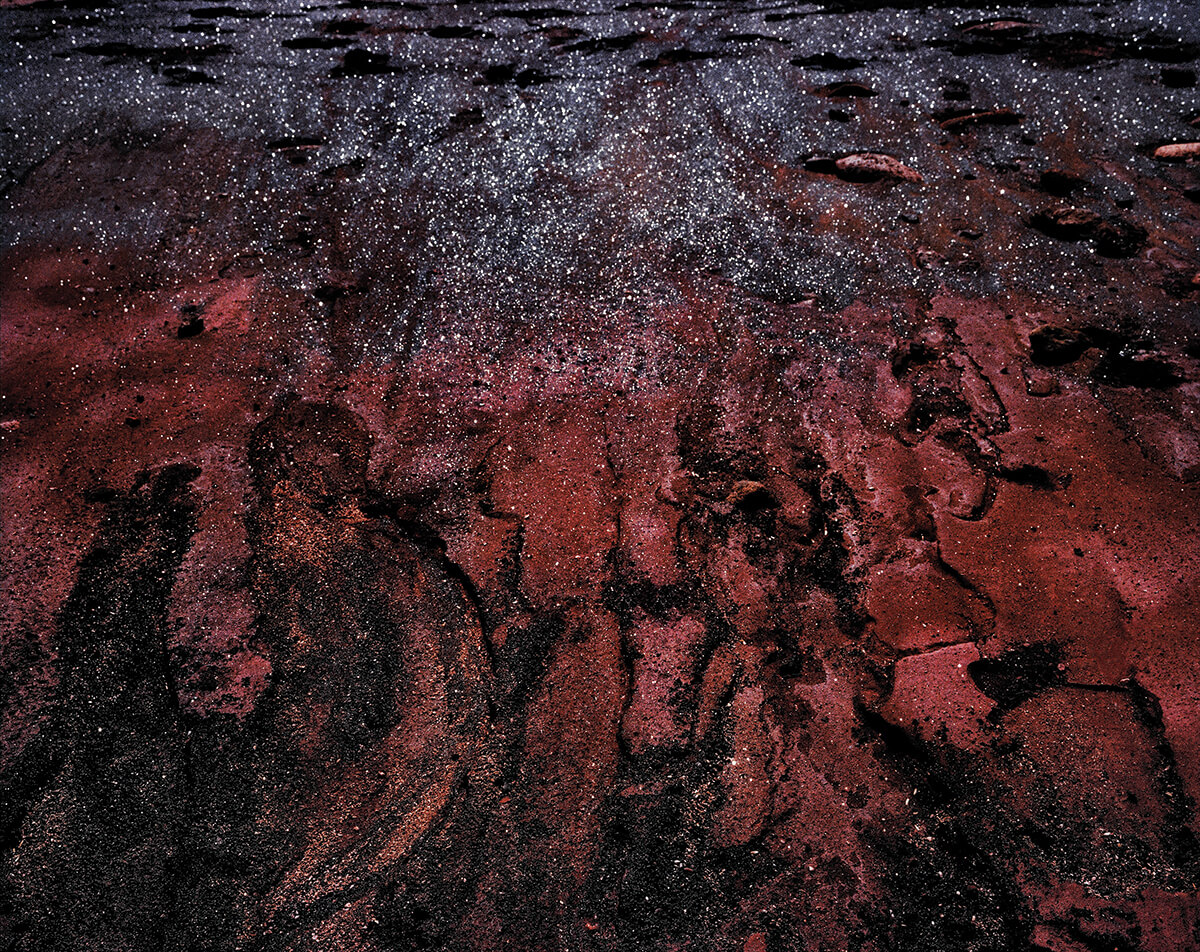

With my work in general, I usually have a larger concept, story or feeling in mind that I’m trying to capture, and my choice of image will reflect that. I tend to think of each scene as in dialogue with the rest, and depending on the visual language that I’m aiming for, I’ll set up the scene differently. For example, in my current series, In the Exodus, I love you more, one of the underlying themes concerns the notion of “presence and absence”, or the idea that our experience can relate to both the surface and depth of things. So I have adopted a visual language in this series’ images that relates to both aspects: to what is both present and absent in our expectations, and to the hidden depth in the surface of things.

What do you think makes photography an effective medium for exploring issues of identity?

Like other art-mediums, with photography, exploring questions about identity is inseparable from questions about truth and representation. Photography es- pecially has a reputation for being a “vehicle” of truth—a way of capturing reality-as-it-is. But as I have suggested earlier about my Iran series, I am also interested in this idea that the surface both reveals and conceals. I like to explore questions about representation and identity through inverting certain expectations about what we normally see, and even hinting at the idea that what is more true is what is absent from the picture.

What made you use photography as a means for analysing your relationship with your homeland and as a medium for storytelling?

Since moving to Australia, photography has become a way for me to tell my story of migration, to explore themes about home and exile, foreignness, belonging, and more specifically, how cultural identity influences our art and daily experiences. For me, it’s impossible to separate my image-making from the sense of familiarity I feel towards a particular place, and this is also reflected in the work I make when I return home to Iran. Photography for me has become a way of reading, seeing and making sense of the world, and of my own being and experiences—including my experience of diaspora.

Does part of the significance of your series ‘In the Exodus, I love you more’ come from its condition as an ongoing series? Or is it a project you’d like to ‘conclude’ one day?

Exactly—because the focus of this series involves exploring my changing rela- tionship to Iran, I could continue adding to it for the rest of my life. I can’t re- ally imagine what its conclusion would be, and I’ve loved the process of discovering something new each time I return to Iran to add to the series. But part of my aim with the work has also been to develop a certain way of “seeing” as an insider-outsider, and after several returns I feel more comfortable and familiar with the language that I have developed. So perhaps this chapter will conclude when I feel that this language is no longer useful for discovering any- thing new—when it has exhausted itself.

What do you think makes distance and migration change our perspective of our origins? Do you think it makes some things clearer, or is it affected by nostalgia?

Migration is something that shatters your world, and transforms your worldview. The pain of being uprooted and of setting down roots elsewhere gives rise to a peculiar sense of homelessness, of not fully belonging, that you never really get over. It’s a strange, liminal existence, but it also gives you a particular kind of vision: a way of seeing the entire world as a foreign land, as Edward Said puts it. That’s something I’ve tried to embrace, rather than clinging nostalgically to my image of “home” or to a narrative of painful “exile”. Instead, I’m interested in exploring this in-between state as a mode of being that is closely tied to the modern condition of homelessness. I’m also fascinated by this idea that things can become nearer the more you draw distant, and vice versa—the play of presence and absence.

Does your work seek in any way to provide an alternative narrative to the dominant representations of your country?

I think most people will accept that the dominant Western media representations of Iran are as much a reflection of the political relations between Iran and the West as anything else. It is a country that is often deliberately misrepresented for political and economic reasons, or simply because of orientalist fantasies. But I also find that many artists’ attempts to directly “correct” these representations can be just as misleading. My view is that exploring personal narratives is a better approach than one that attempts to address the question of true-versus-false representations head on, which is just to say that, when we are talking about a place like Iran—or like anywhere, probably—there is no “single” reality that can be captured. My images of Iran reflect my experiences, and they will be quite different to those of the family of a martyr or political prisoner, say, or someone living on the margins of society. This is, I suppose, one of the ideas that I’m consciously exploring through my series—the idea that all image-making or story-telling is situated and perspectival in this way, but that such perspectival story-telling, perhaps, contains more truth than grand narratives or generalising statements.

The interview was originally published in www.pantamagazine.com

Interview by Guille Lasarte