TEST SITE FOR ART & HOSPITALITY EXPERIENCES

I Work & Live Everywhere

Interview with German-Syrian artist Manaf Halbouni

21.01.2021

On the occasion of his solo exhibition Level 3, at Zilberman Gallery, Berlin, we spoke with Manaf Halbouni about home and travelling between cultures in space and time.

Where About Now: Where are you right now?

Manaf Halbouni: I moved to Berlin 2 months ago, so that’s where I am now.

WAN: It must be a strange time to move. How was the move for you?

MH: I was really lucky to find something after searching for almost 7 months. I took the decision already last year to move out of Dresden and then the pandemic made the decision even stronger, I felt like I needed a new start and I was getting bored in Dresden.

WAN: You grew up in Damascus and you’re half German, half Syrian. Can you tell us about how those two cultures reflect in your artwork and personal life?

MH: I lived 23 years in Damascus and I finished my first art study there. Then I moved to Dresden, the city where my mom is from, to avoid going to the military in Syria. Then I started my second art study at the HfBK Dresden. Being part of these two cultures my whole life is always something that goes into my work because I always try to combine things that are happening there with things that are happening here. But I’m more of an observer, I look at what people are doing and what reactions are happening in society. I’m very much interested with borders, human movement and social change. I always try to show my work as a story which you can tell yourself and I like to play with irony. I like it when it’s not necessary for me to be in front of the work and explain what it means, and prefer when the material itself tells you something because you can relate to it or it tells you a story. There is always a connection in my work to where I grew up because I know Germany and Syria from my childhood - we were always visiting my grandparents in Germany in the summer - so I was always living between two cultures.

WAN: Yeah, it’s quite prevalent in your work this being between two cultures. I want to talk about your solo show in Berlin at Zilberman Gallery, Level 3. In one of your works ULTUR (2020) you replace the K of Kultur with the Arabic letter Kaf. In just one word you bridge a linguistic and cultural divide. How was growing up with these two languages and cultures influenced you?

MH: I grew up in Syria, in Damascus, and at home we were always speaking German including my father. That’s one of the reasons why I don’t really have an accent when I speak German. My parents decided that we would only speak German at home, so inside the flat we were in a German enclave and only outside we would speak Arabic. So, for me when I hear these languages there’s nothing changing in my mind in terms of understanding. I can switch from German to Arabic really fast. In fact, when I hear people speaking this mixed German and Arabic in one sentence, I can understand it as if it was spoken in just one language. That’s one of the reasons I did this work with Kultur. When I see the Arabic K, I don’t notice whether it’s an Arabic K or a Latin K, I just read it as Kultur. But someone who didn’t grow up with Arabic will just read ultur and have to guess what the first symbol is. It’s quite interesting for me to see how people react who grew up with both languages and those who only had one. Last year I had a residency in a refugee camp in Berlin, in Marzahn, and I was living there in the camp for a month. Mainly I was working with the kids because they were there the whole time. And that’s where I also noticed this mixed German, like 3, 4, 5 Arabic words and then 3 other German words after. It was super fun to see how they are growing up with these mixed languages. So maybe it’s a migration thing where you always grow up with two languages, two cultures.

WAN: Well, I suppose every culture is a hybrid in a way, we borrow and are influenced by what’s around us. So maybe this specific German-Arabic hybrid is where you most feel at home?

MH: Well, home is a really weird word. I’ve been asking myself for many years where do I belong? And I came to the conclusion that I don’t belong anywhere. In Syria, I’m a foreigner, and in Germany I’m also a foreigner, at least until you hear me speaking. But when my name is written anywhere, like on a list, I don’t get the best cards. Especially when I was searching for a flat here. So it’s nice being this hybrid as I can live between the worlds, taking part from here and part from there and trying to do something better.

WAN: Your CV states that you live everywhere. What does that mean?

MH: Yes, I refuse to say that I’m living at one point because I really work everywhere. I’m always trying to travel and do my shows all over. The last few years I was always somewhere else doing projects or for my exhibitions, so I was never in one place. And that’s me - I don’t specifically work in one city, I just need a harbor where I can go back and collect some stuff and continue sailing out again. At the moment the harbor is Berlin but I work and live everywhere.

WAN: I can imagine that travelling routine has been affected by the pandemic. How has that change been for you?

MH: Oh, yeah. It’s weird because when the pandemic started in March, I already had 3 trips planned, an art show in Dubai and also Sofia, Bulgaria and then my solo show got postponed. So there was a lot in the plans and then I got stuck in one place for 3 months which was quite unusual. I think it was the first time in a long time being so long in Dresden. Normally I was just 1 month in Dresden and then on the road again.

WAN: And what was it like to be so long in Dresden?

MH: I spent a lot of time in the studio and actually all the works in Level 3 were made during this period, from March to June.

WAN: So it was productive at least.

MH: Yes, very much. Mostly gallery things but I also made plans for some bigger projects.

WAN: Sounds exciting! I wanted to talk more about the series What If… which also feature in Level 3. It’s a really interesting work which has been going on for a while now, right?

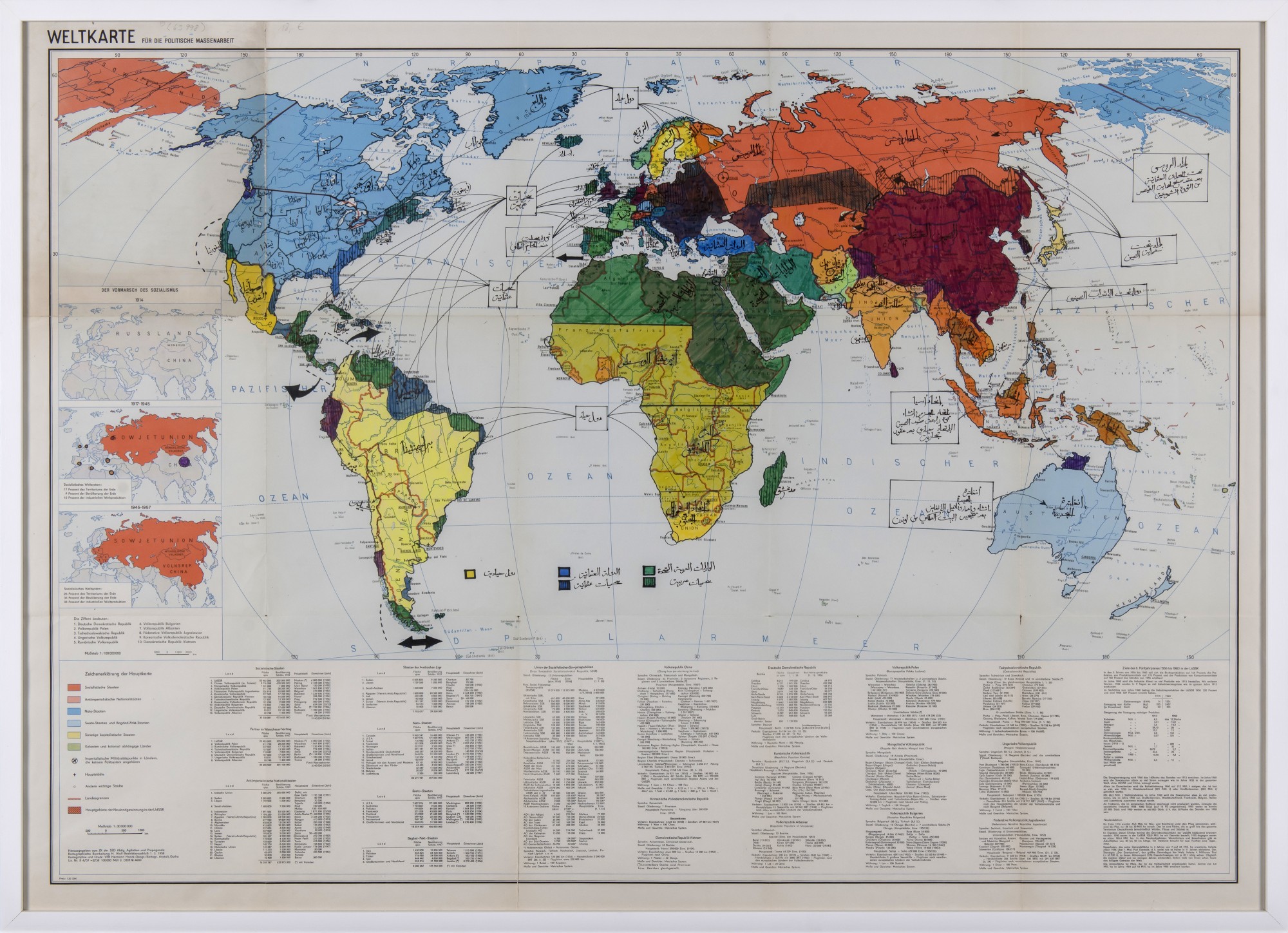

MH: Yes, it’s an ongoing project and probably it will never end. I started it in 2015 as a play about something with which I was annoyed - the Sykes-Picot agreement. It was signed between Britain and France and divided the Middle East into the countries which exist today. It was in 1916 and was a secret agreement. So starting from this, I took a European map out of the atlas and started drawing borders and lines and said, “Here everything is divided into colonies”, for example. But it was not consequent enough to just take maps and draw lines on them. I needed to give the story a character, so I invented a fake general. I imagined the Industrial Revolution in 1845 didn’t happen in London but it happened in the Middle East, in the Ottoman Empire and the Arabic States. So I took the Ottoman Empire and split from it the United States of Arabia.

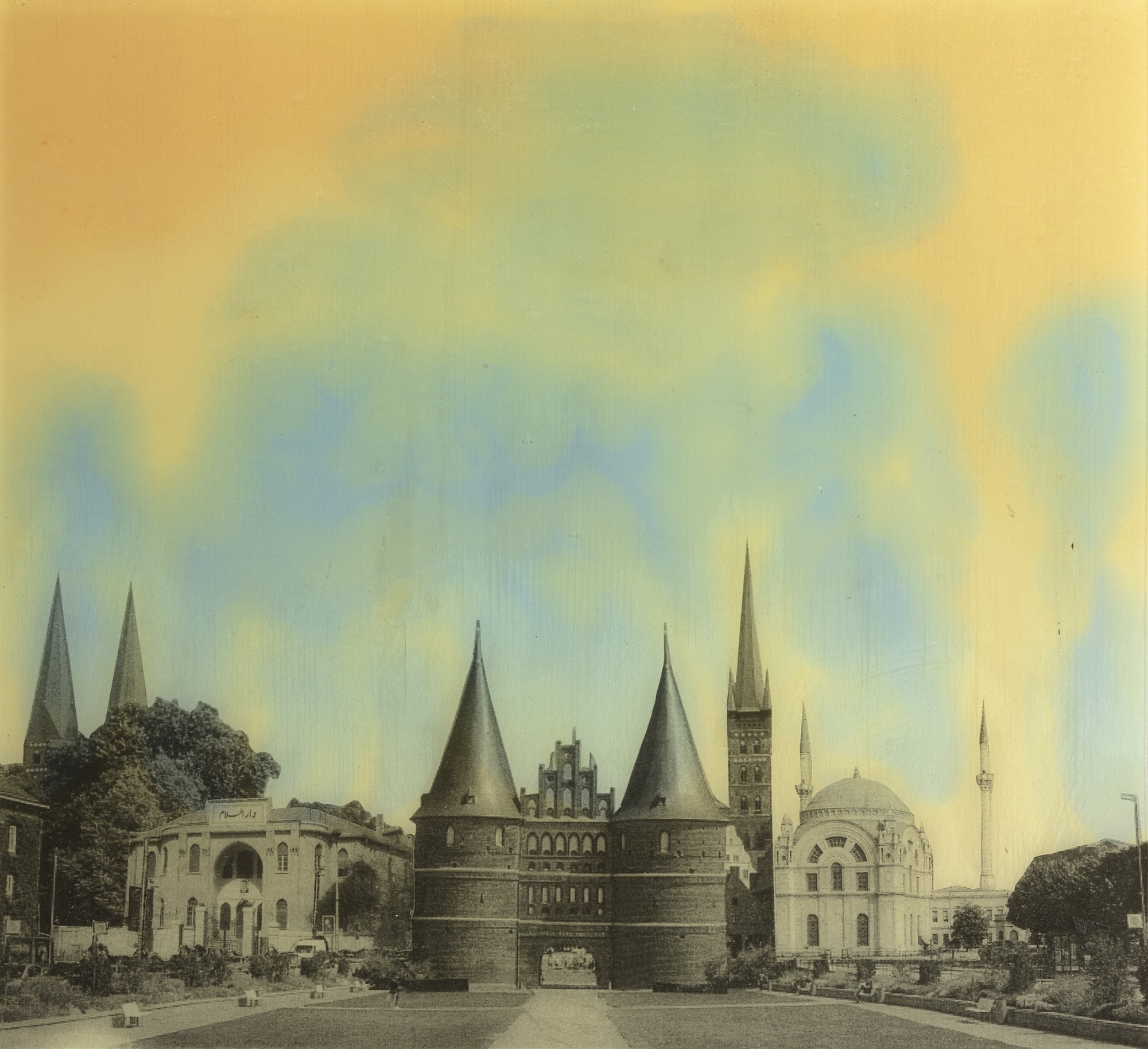

Those are the two big industrial nations apart from the Chinese. I made the Ottoman Empire and the United States of Arabia colonize Europe. Now the borders became more realistic, but I wanted to tell the story from one person’s perspective. so I sent this general, Yusuf Hadid, to the Protectorate of Saxony to help the Saxonian king to free Dresden from a revolution that was happening in North Germany. This is happening in the 1920s and later on, like 30 years later, the United States of Arabia starts to create new nations like the Republic of Hansa. I’m always writing stories and I have a diary of the General of which 10 pages are online on my website (only in German, unfortunately), where he talks about moving with his army through Dresden. So this is one part of the work and the other part I started doing portraits. So one work is a 2-channel video installation where the general is on 2 displays and I’m playing with quotes, on one screen he is saying “I have a dream” and on the other one, “Yes we can”. There are also maps of the general’s movements. The newest things I did are the collages where I change city views and buildings into something different where history can really change things.

WAN: It’s such an interesting thought experiment. It goes to show that things we consider so solid like borders and history are actually fluid and can be influenced by a single action. Has this thought exercise changed your perception on anything?

MH: Nothing has changed for me personally, rather, I wanted to help others to imagine how it could have been the other way. You can question everything, even the story I’m telling because I’m human and I make mistakes but still I’m trying to provoke the imagination. I realized recently that I should actually be using the Islamic lunar calendar when I write in the general’s diary instead of the European calendar, so I’m also trying to improve.

WAN: Well, it seems like there’s a lot to expand on this project which is why it keeps going on.

MH: Yes, definitely I’m also planning the next video projects I will work on as part of the series.

WAN: It’s interesting this idea of getting people to imagine how things could have been otherwise. It reminds me of your quite well-known work Monument(2017) in which you drew a connection between what is happening now in Aleppo and the history of the war in Dresden. The work also sparked quite an outrage. Were you prepared for that? And what was the controversy about?

MH: I was kind of prepared that this project would annoy people but I didn’t expect it to be so much. I was expecting a wave and it was a tsunami in the end. But I’m okay with that and I know with some of my previous projects that I annoy people with the things I do and you just have to find a way to deal with that and start discussions with them. That’s one of the main purposes why I’m doing this, I want people to talk to each other. And with the busses this definitely happened, not only in Dresden but all over, and the whole project was just trying to show the effects of history. Aleppo is being destroyed in the war in Syria and something similar happened in Germany 70 years ago but people just forgot it and show no empathy and that annoyed me. The 13th of February in Dresden is quite a heavy day and every year they discuss how to deal with these memories. I wanted to propose a new way by showing images of a place where it’s happening at the moment. That was my main purpose with the work. Also to show hope to people from Syria and that after destruction there is reconstruction. Dresden is completely reconstructed and now it’s like Disneyland but at least it looks clean, and this is probably something that will also happen in Aleppo but we just don’t know when. It took a lot of time in Dresden.

WAN: Can you tell us about any new projects coming up?

MH: Yes, I’ll have another solo show in May in Soest at the Wilhelm Morgner Museum and I’m gonna do a public art installation there in addition to the museum show.

Level 3 is on view at Zilberman Gallery Berlin.

All images: Courtesy Manaf Halbouni and Zilberman, Istanbul/Berlin. Photo: Chroma

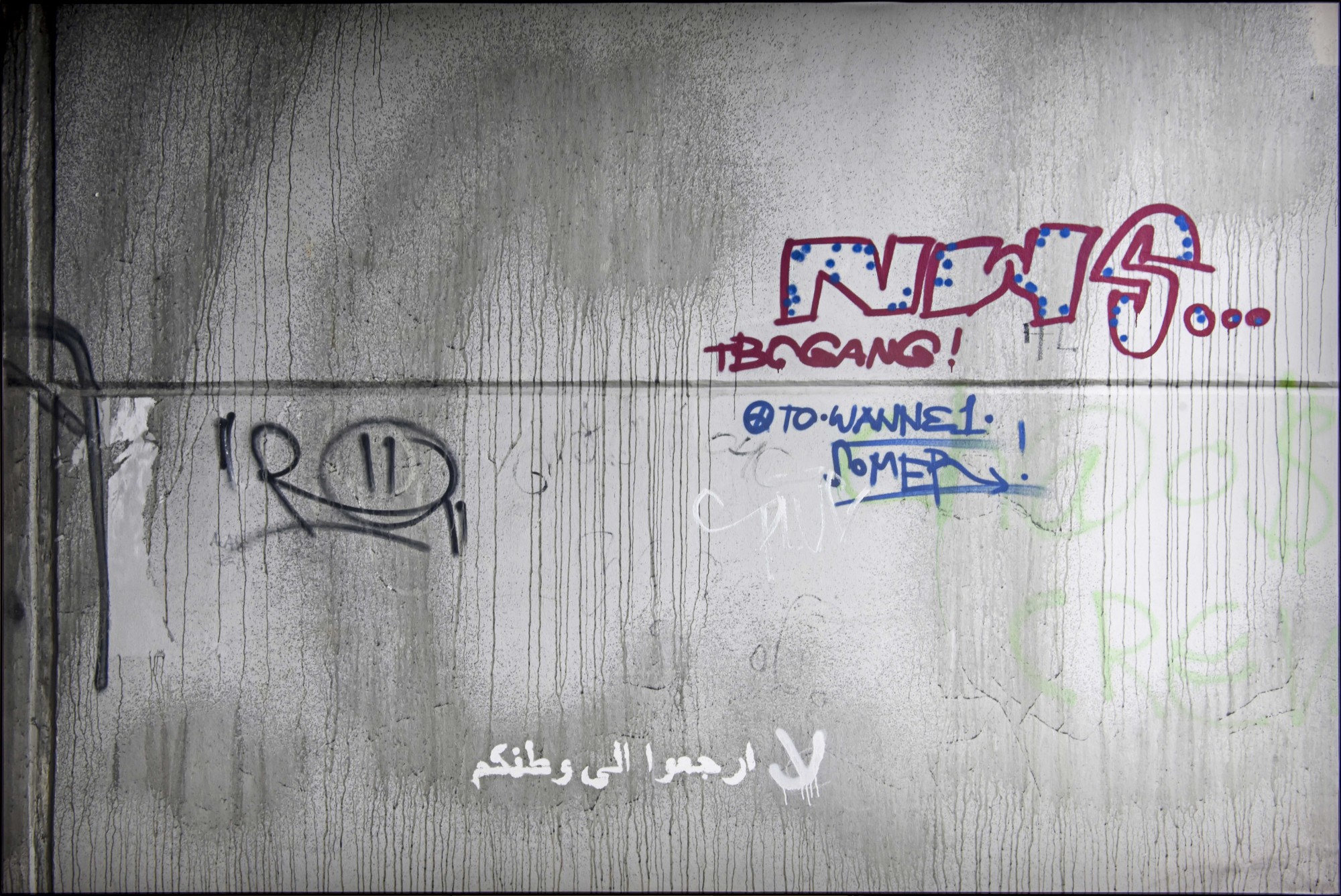

Header image: GO HOME – not realized public art project, 2019. Carbon print / Kohlenstoffdruck. 60 x 45 cm. Original Photograph: Dirk Vorderstraße. Courtesy Manaf Halbouni and Zilberman, Istanbul/Berlin.